The search for Hannah Crafts

January 31, 2024

A new book tells the story of the North Carolina native who authored the first known novel by an African American woman.

by Jason Miller

A disheveled manuscript titled The Bondwoman’s Narrative was listed only as “Lot 30: Unpublished Original Manuscript” when it appeared in a Swann Auction Galleries catalog in 2001. Written between 1853-1859, few people knew the hand-sewn pages pressed between two boards even existed. Barely meeting its retainer, the manuscript received only one bid.

But the novel became a bestseller when it was published in 2002, after being quietly purchased and then authenticated by esteemed historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. Soon after, news began to spread that this was the first known novel written by an African American woman.

Amid the speculation entered Gregg Hecimovich, an English professor at Furman University in Greenville, S.C., who is currently serving as Hutchins Family Fellow at Harvard University. Skeptical at first, Hecimovich devoted two decades of work to solving that mystery — and his book The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts, published in October, reveals more about the writer’s identity and true marvel of her work.

“She became a New York Times bestselling author because of the sheer genius of the work,” Hecimovich says. “The novel itself is profound, artistic and funny. It’s a page-turner.”

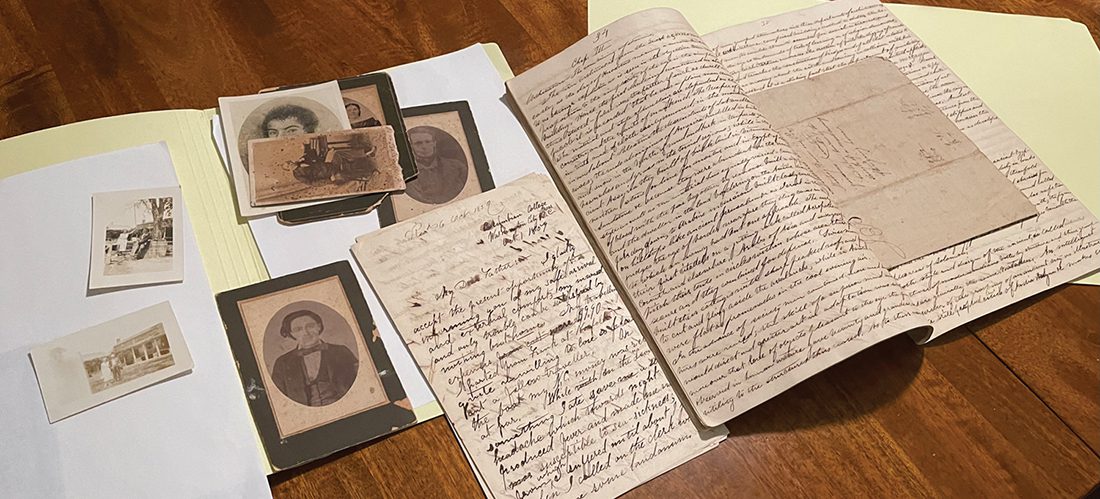

There’s only one handwritten copy in existence, written solely by the author herself — an enslaved Black woman — on paper secreted away from her captors, with letters scripted using a goose quill lifted from an inkwell. Revisions were made by pasting slips of paper in place with a thimble — you can see the dimple marks it left behind on the manuscript. The completed pages were sewn together between twin boards that serve as its makeshift covers.

Bottom right: Slave records that include Hannah and her relatives.

In his book, Hecimovich allows us to see Crafts at the very moment she chooses to name her captors. John Hill Wheeler was a lawyer, politician and planter from Murfreesboro, in northeastern North Carolina. After risking a hard-won freedom via the Underground Railroad in 1857, Crafts finally had her first chance to write his name without fear. Where her original manuscript read “Wh—r,” Crafts now found the courage to add the letters “eele” above that dash to spell “Wheeler.”

Uncovering Crafts’ identity required locating overlooked property records, conducting extensive forensic paper analysis, and even studying handwritten notes made on the backs of ignored calendars. These combined to form “a series of Chinese lanterns that lit a path,” Hecimovich says. Many of the documents are more than 170 years old. Hecimovich gently turned every one.

When Hecimovich began his quest in 2002, many experts were highly skeptical that an enslaved woman could have written such a remarkable novel. In going through the archival records, he had a realization. “There was a moment happening in the margins of the enslavers’ papers and journal entries that earlier generations of scholars weren’t really paying attention to.” Crafts’ identity was most often represented as an “X” on ledgers, but Hecimovich noticed the entries located on the backs of day calendars at the Library of Congress, where John Wheeler wrote down the actual names of his captives. This was the clue Hecimovich needed. With a new purpose, he found himself repeatedly drawn to Bertie County, N.C., to listen and learn from the descendent communities.

In her novel, Crafts prominently included a famous grouping of trees near the plantation where she was born in Bertie County known as “The Gospel Oaks.” The final one of these trees fell in November of 2011. While standing there, Hecimovich received a phone call. Divinely, he learned that a letter had been found linking the author to a farm where she found her freedom in New York State. It allowed Hecimovich to definitively confirm Crafts’ identity as the author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative. Standing by that fallen tree, the land seemed to have one last story to tell.

Such literacy has been “overlooked by scholars who turned their back on it,” says longtime preservationist and Bertie County historian Benjamin Speller. “It means a lot that the academic communication channels and the gatekeepers are finally paying attention,” he says. “Something of this kind of historical importance should have been picked up a long time ago — and [there are] more stories like this still out there.” SP

Photographs courtesy Gregg Hecimovich