One love

November 1, 2021

Before The Peninsula, River Run and Trump National, there was Lakeview Country Club. All were welcome.

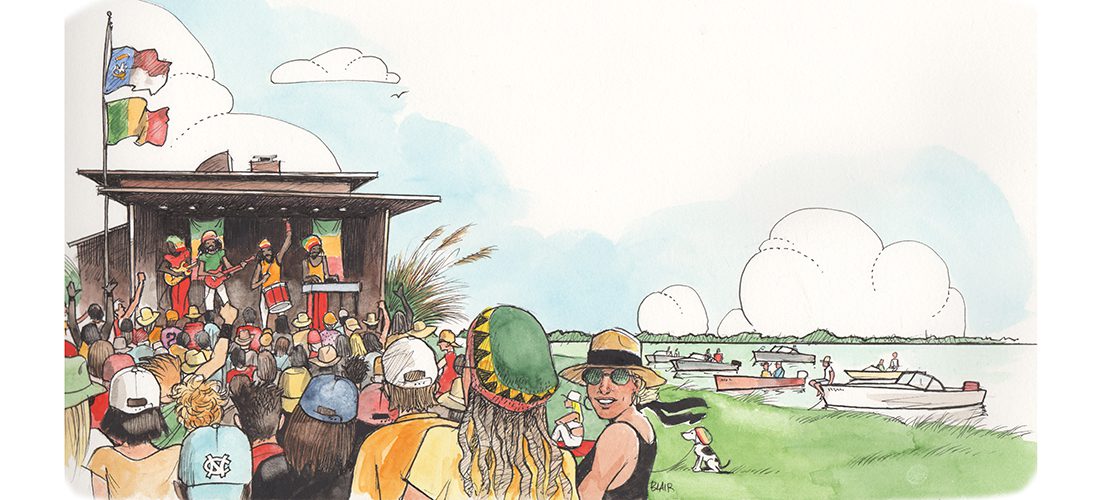

by Page Leggett • illustrations by Harry Blair

Lake Norman wasn’t always populated by NASCAR drivers, waterfront mansions and the Trump National Golf Club. It used to be a decidedly unfancy weekend retreat. Lots of families who lived in 28207 and 28211 had getaways on the lake. Some of them were little more than trailers and a dock. Heck, some of them were actual trailers.

In the 1980s and prior, there was nothing upscale about the man-made (by Duke Energy) lake. It was a getaway — a place you’d retreat for a shorts-and-T-shirt-and-flip-flops weekend. My parents had a lovable lakefront shack they shared with two other families. (True story: Through a series of unfortunate renovations that predated their acquisition of the home, the foyer was also a bathroom.)

Driving up Interstate 77 to the lake, we’d stop at an independent video store attached to a gas station at Exit 33 and stock up on VHS tapes for the weekend. There wasn’t much else to do.

There certainly weren’t any country clubs.

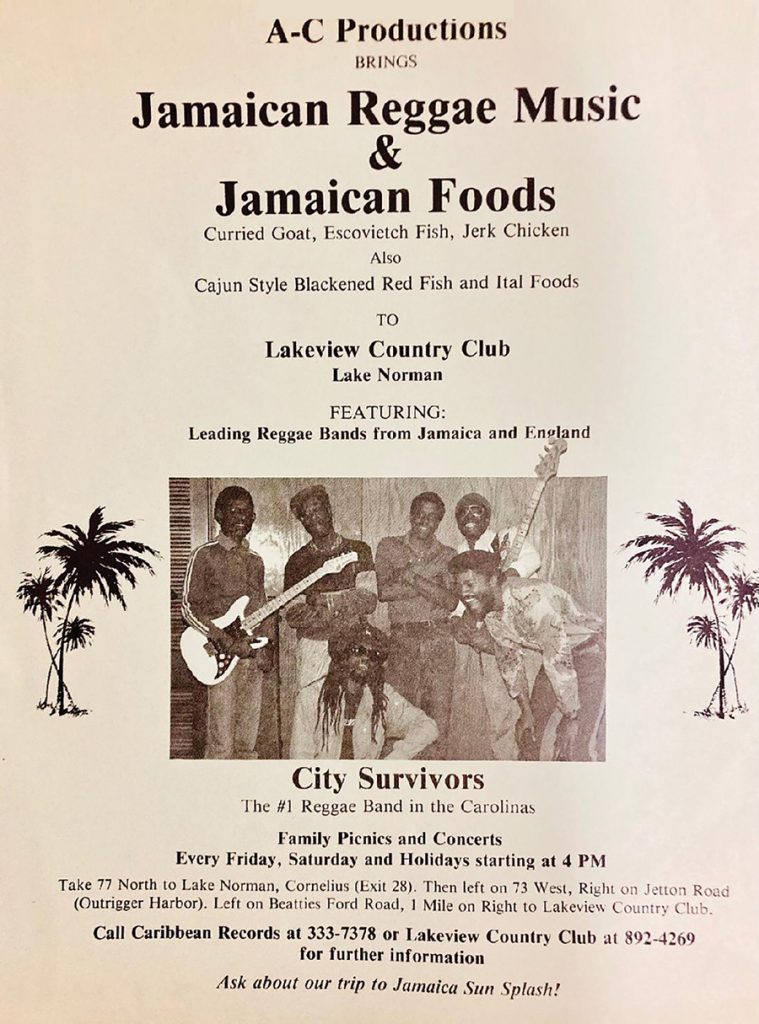

Well … there was one. But it was a “country club” in name only. There wasn’t a vetting process to become a member. In fact, there wasn’t even a membership fee. Just a small cover charge when a reggae band — Awareness Art Ensemble, Burning Spear, Moja Nya or Rolly Gray and Sunfire — performed.

Lakeview Country Club, accessed by car from Exit 28 off I-77, was a circa-1972 cinder-block building originally known as the Connor Family Recreation Center, or Connors’ Place. The building and the land were owned by the late John Connor, a prominent Black businessman in Cornelius. (John Connor Road, off Jetton Road near The Peninsula Yacht Club, is named for him.) The club became legendary — and not just around Lake Norman — because of the reggae concerts held there.

‘People came from everywhere’

“It started with local bands like City Survivors,” recalls Carolyn Barber, owner of Reggae Central, which has been a Plaza Midwood mainstay for 25 years, and a concert promoter in the 1980s and ’90s. “And then, we started doing international reggae artists.” The oldest concert poster she still has dates to March 29, 1986.

Bentley James, who owned the Caribbean Records store in Latta Arcade, got the whole thing started, Barber says. Barber took over as promoter after James returned to his native Jamaica in the 1990s.

Svend Deal, a lawyer now living in Tuxedo in the North Carolina mountains, grew up as the youngest of five boys in Myers Park. His memories of Lakeview are a little hazy, given the passage of time and his beer consumption each time he made the trip up I-77 to where The Peninsula — an actual country club — now stands.

But his memories from high-school days seem remarkably clear.

“It looked like a typical VFW Post,” Deal says. “They always had jerk chicken or curried goat, rice and peas. It was served on a paper plate, and you ate it with a plastic fork. You could get a Red Stripe for maybe $1.50 — but you had to have cash money.” I ask Deal if it was a little like Belle Acres Golf & Country Club, the legendary South Boulevard spot famous for its french fries, putt-putt course and a waiting list that never ends. “Oh, this was nowhere near as nice as Belle Acres,” Deal says.

Nevertheless, Deal and his crew would take his dad’s ski boat, a 1989 Malibu Euro F3, to the Lakeview cove, pull up on the beach (if there was room) and pay the nominal cover charge. In Deal’s mind — and maybe in actuality — there were sometimes hundreds of boats. Not everyone got to park on the beach.

“Oh, there were so many boats,” Barber recalls. “When you got out of your boat, you might have to swim the rest of the way. We collected a lot of wet money.”

The club was just beyond Hunters Chapel United Methodist Church — the Connors’ place of worship, Barber recalls — on what it is now John Connor Road. It’s so legendary that even Google Maps shows the area as “Reggae Cove” and lists it as a tourist attraction. (It’s not … anymore.)

In addition to the music, there was reggae merch. “We had vendors set up,” Barber says. “You could sell whatever you made. And people came from everywhere. You wouldn’t believe. People came from D.C. People came from Virginia. People came from Charleston. Everywhere.”

By all accounts, the outdoor concerts could be massive, festival-style gatherings. No one can recall exactly how many people might turn out. “Five hundred,” Deal says. “That’s my drunk estimate, anyway.”

There were the Connors and their friends. “[John Connor] used to drive his golf cart around while everything was going on,” Barber says. And there were the kids from East Mecklenburg, Myers Park and West Charlotte high schools, who came in droves.

‘There to have a good time’

“It was totally safe,” Deal recalls. “There were never any fights. No one gave us the stink eye. We were all there to have a good time, dance and listen to the music. It was always super chill.”

Dave Rickard, now vice president at Carolina Made Inc., a wholesale sportswear distributor based in Indian Trail, was a student at East Mecklenburg High School in the mid-1980s when a friend’s older brother told him about Lakeview. He and Deal never met (not that they recall), but chances are, they visited the club at the same time.

“Everybody got along,” Rickard says. His love for Bob Marley and Peter Tosh grew into a love of all reggae. The music at Lakeview was the draw, but even as a teenager, Rickard appreciated the club’s vibe.

“There were people from all walks of life,” he continues. “You had white people, Black people, old people, young people, lots of people that were obviously into the whole reggae scene with dreadlocks and tie-dyes. But then there [were] also lots of yuppie kids there. It was a little bit of everything — everyone getting along and grooving, just having fun.”

So how did Deal, Rickard and others get away with going to a bar and concert venue when they were underage?

“Some people would tell their parents they were going to a friend’s parents’ country club,” Rickard says. (It wasn’t a total lie.) “And the parents would think, ‘Oh, good. Junior’s finally getting some class.’”

Rickard and his wife, Jodi, who was his best friend during their East Meck days, recall bringing their own coolers to the concerts. Deal remembers buying beer at the club. Maybe there was a little of both. People brought their own blankets and lawn chairs — there was a stage but no seating.

“People would bring a tent and camp out all night long,” Barber recalls. “There was no fighting — there was just peace and love. That’s what it was all about.” SP