Heal Charlotte connects grassroots organizations to people in need, forwarding its mission to build a better city.

by Vanessa Infanzon

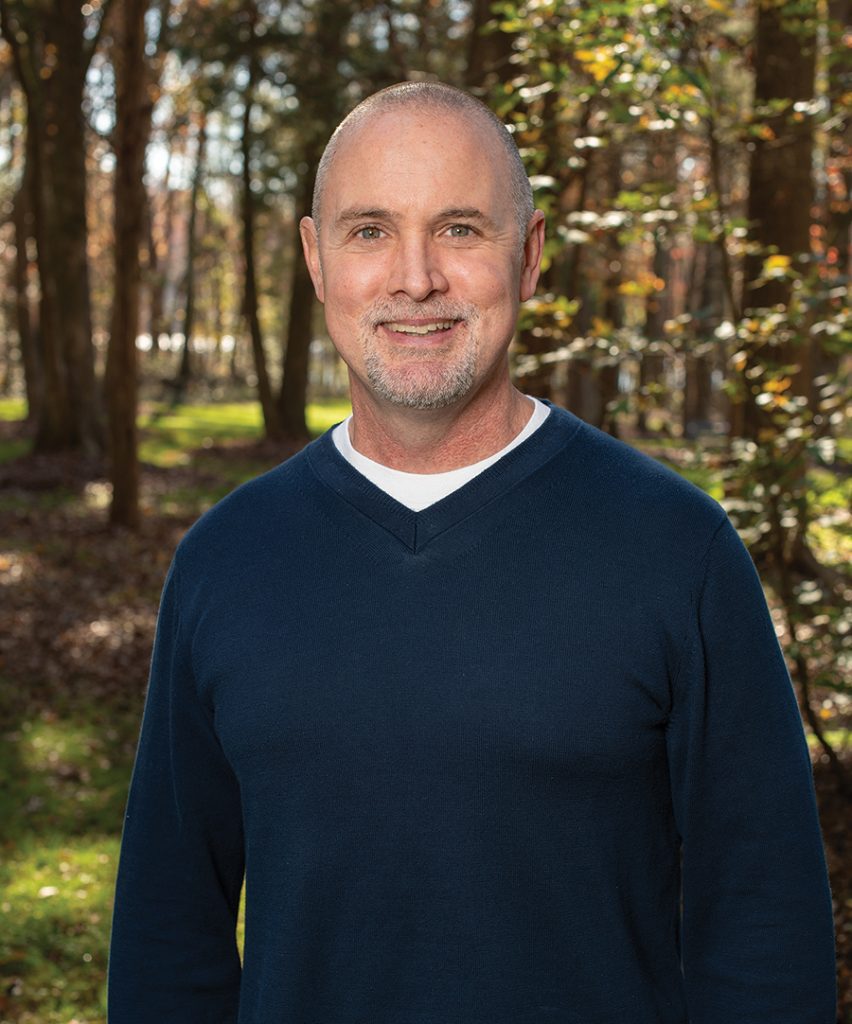

As Greg Jackson walks through the glass doors into the lobby of the Baymont Inn, a two-story motel off Sugar Creek Road in northeast Charlotte, his positive energy is immediate. Dressed in a hat and T-shirt emblazoned with the logo for Heal Charlotte, a nonprofit Jackson founded in 2017, it’s impossible not to be drawn into his aura.

Since forming Heal Charlotte, Jackson, his staff and a team of volunteers and board members, most notably Anthony Morrow, former NBA player and Charlotte native, work on several fronts: Stop the Violence, a gun-violence prevention program; an afterschool program at Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School; and its largest task to date, a $10 million capital campaign to purchase the Baymont Inn to house homeless families.

Jackson moved to Charlotte in 2009 from the Bronx in New York City. Prior to Heal Charlotte, he was a sous chef and hip-hop artist. When he has the time, he still records Christian hip-hop music.

As the organization’s executive director, Jackson is the first person to say progress won’t happen on his own. In fact, the partnerships Heal Charlotte has developed throughout the city supports his mantra: “If everybody does a little, no one will have to do a lot.”

The afterschool program started this fall. It’s an example of several Charlotte entities coming together. When MeckEd, a nonprofit education fund, received a grant through the city’s SAFE Charlotte program, it partnered with Heal Charlotte and Digi-Bridge, a local nonprofit that promotes STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts and math) education. Other grassroots organizations such as Men of Destiny, Promise Youth Development and Urban Institute for Strengthening Families support the program.

The funding provides two instructors and a staffer to collect data. As many as 40 students participate in a three-hour program every day after school. “Most of the kids we’re serving have a one-parent home,” Jackson says. “Some of the kids stay in hotels, and they need this out-of-school time, especially coming out of the pandemic.”

The funding gave the group of planners time to collaborate and develop ideas. “[Ideation time] is not as common in the nonprofit world,” Jackson explains. “We need that time before the program starts to sit down and [discuss] how we are going to be aligned, have the same values and same messaging. I am very grateful for that time, because normally we are just responding to what’s happening in the neighborhood.”

Wednesdays through Fridays, students learn about STEAM, economic mobility, etiquette and gardening through Digi-Bridge and MeckEd. Mondays and Tuesdays at the afterschool program are dedicated to Heal Charlotte’s lessons about gun-violence prevention and being village minded, drawing upon African American culture.

Students read The Hate U Give, a young-adult novel by Angie Thomas about a fatal police-involved shooting, and listen to songs by rap artists Kendrick Lamar and Little Baby to explore lyrics. “[Little Baby] is an artist these kids listen to, but they probably don’t listen to these songs,” Jackson says. “We’re going to go through the songs [and talk about] what these lyrics mean to them, understand their culture as young people and [how to] control the narrative. We’re teaching them to be positive change agents.”

Additional federal funding pays for a social worker from Christ Centered Community Counseling to be available for the students. According to Jackson, 60% of the students in the after-school program don’t feel safe at school; several know someone who has been shot. “C4 is there when we have rough conversations,” Jackson says.

In the past two years, Heal Charlotte has housed 41 families for 90 to 120 days at the Baymont Inn. The program helps families save money for rent and gives them the tools to sustain a home. Sixty-one percent transitioned to permanent housing. After an intake process, each family receives a laptop from E2D, financial literacy help from Common Wealth Charlotte and workforce development skills from Urban League of Central Carolinas. Through a federally funded program, Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools provides a bus for the children. “We do take a holistic approach to everything we’re doing,” Jackson says. “We recognize that if we house someone, that’s not the end all, be all. There are a lot more components to people getting back into permanent housing.”

Brent Jones, executive director of service and outreach at StoneBridge Church Community, a Presbyterian Church in America affiliate with about 500 members in northeast Charlotte, met Jackson a few times between 2016 and 2020. But the partnership began when Heal Charlotte needed help delivering meals to families during the pandemic. Church members jumped in to assist.

Now, you’ll find Jones driving students home from the after-school program in the church bus. And most recently, the congregation donated $150,000 to Heal Charlotte’s housing program, enough to fund 15 families this winter at the Baymont Inn.

Seeing Jackson’s interactions firsthand during the George Floyd protests in 2020 left a lasting impact on Jones. “I remember Greg standing literally between the group of protesters and a line of CMPD (Charlotte Mecklenburg Police Department) officers,” Jones says. “Greg [was] diffusing the situation, talking down what could have escalated into a violent situation. He’s the only one I can think of who has the utmost of respect in both the community and in the halls of city government.” SP