A photographic journey about connecting with the past, returning to the familiar, and seeking greater meaning in the places along the way.

photographs by Richard Israel | written by Whitley Adkins

For my whole life, I’ve been making that South Carolina back-roads trek to the beach. Depending on the destination — Pawleys Island, Myrtle Beach or Charleston — the exact route varies. But one thing has always stayed the same: avoiding interstates and busy highways as much as possible, choosing instead the magical mystery and scenery of those quiet, country roads.

From my youngest years, I vividly remember riding in the back seat of my dad’s 1979 silver Volkswagen Bug convertible, my baby-fine hair blowing uncontrollably every which way. As I got older, I’d ride next to him in the passenger seat, my hair wrapped in a navy or red bandana (which my father, always so gentlemanlike, kept tucked inside the door flap for any female passengers). Working in real estate at Debordieu Colony, a family-friendly coastal community popular with many Charlotteans, he lived in downtown Georgetown during the years leading up to Hurricane Hugo. Dad would go to work, and I would wander the live-oak-lined sidewalks, studying the rich historical homes, both stately and modest, up and down Front Street, wondering what stories those rocking-chair- and joggling-board-lined front porches could tell.

When I was in high school, we took regular trips together to the coast for many a shag-dance competition, often staying at our favorite place, the Sea View Inn. In college, Dad would place a map in the glove box of my car, with highlighter marks tracing the back roads that would take me to my coastal destinations. He also gave me a list of names and telephone numbers of folks he asked me to stop and “call upon” at pay phones along the way. You see, he advised, you never know when you’ll be in need. And one time, as a young adult driving my brand-new, complicated European car in the early evening through tiny Dalzell, S.C., I learned that Dad was right. Thanks to him, on that quiet back road to the beach, I had someone to look out for me.

The author at an abandoned storefront in Sumter.

Today, those roads seem more magical than ever. With two sons of my own, I still make regular trips to the beach with my mom and stepfather. As I encourage my two young boys to take it all in, the farms and fields, stately oaks, old churches, broken-down trucks, and front-porch rockers are even more vivid. And those winding roads and their destinations wrap me in safety and comfort.

Over the last few years, every time I pointed to a tree, house, church or animal, I would say to myself, “I wish Richard were here with me to capture this on camera!” Whenever I’d mention it, his response — in his thick British accent — was always the same. “Oh yeah! Let’s do it. We have to do that!” Photographer Richard Israel and I see things through the same lens. Living in a thriving city with a tear-it-down, make-it-shinier mentality, it’s that messy-but-meaningful, story-filled stuff you can only find on the back roads that we crave.

Finally, on an unrelenting day of rain, we set out to capture all the beautiful things that have caught my eye for the last 45 years from inside the car — to get out and see them more closely, touch them and breathe them in. It was like finally meeting a close family friend or distant relative for the first time.

An old friend at Pawleys Island introduced us to our new friend, artist Zenobia Harper, who would in turn introduce us to a number of fine folks in the Gullah communities surrounding Georgetown, Brown’s Ferry and Pawleys Island. Each of our conversations had a consistent theme: While each had been encouraged to leave their small communities in pursuit of something bigger and better, they all chose to return home. In seeking something shinier, something more, they realized in doing so, they had everything they needed and wanted all along.

This photographic essay is a journey about connecting with the past — imagining towns, buildings and the people that once inhabited them when they were vibrant communities. This story is about seeking greater meaning in familiar places. This story is about coming home.

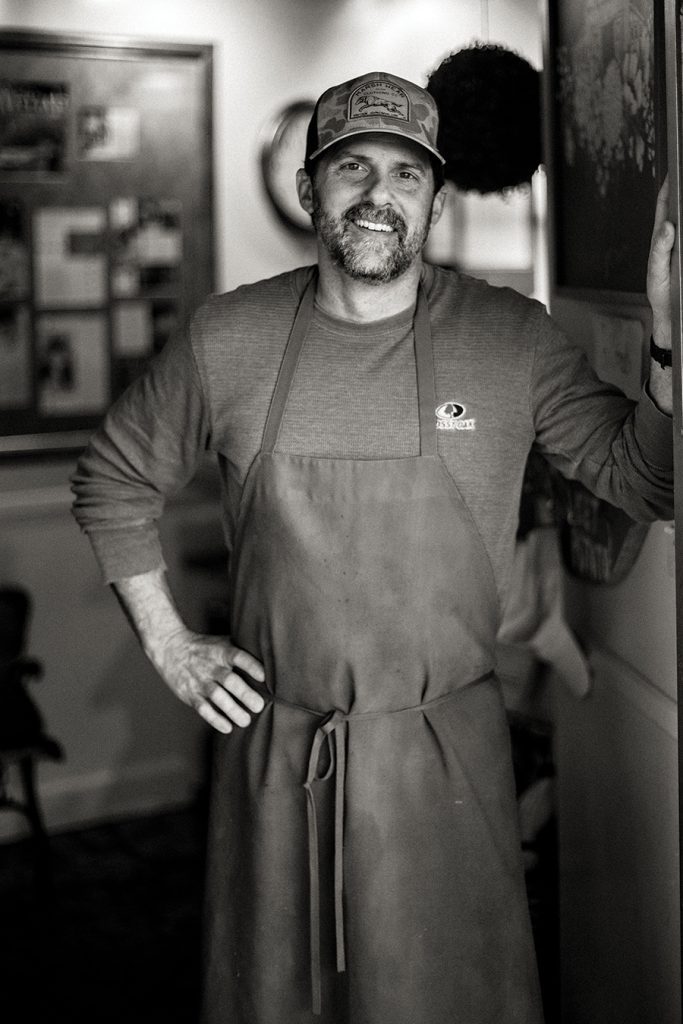

Lilfred’s, a white-tablecloth restaurant and caterer in tiny Rembert; Lilfred’s chef-owner Trent Langston; the menu.

Rembert

The tiny crossroads of Rembert consists of a gas station, car wash, an empty cinderblock building and Lilfred’s. I always wanted to know more about Lilfred’s — I assumed it was a restaurant but never saw any cars outside. On a rainy Wednesday morning, just two vehicles sit on the side of the building. We knock on the door and are greeted by chef-owner Trent Langston. He and his wife Wendy are prepping for tomorrow night’s dinner. Originally a gas station that opened in 1951, the couple now owns the long-standing establishment. The white-tablecloth restaurant serves a $45 four-course meal Thursday-Saturday and caters weddings and other events.

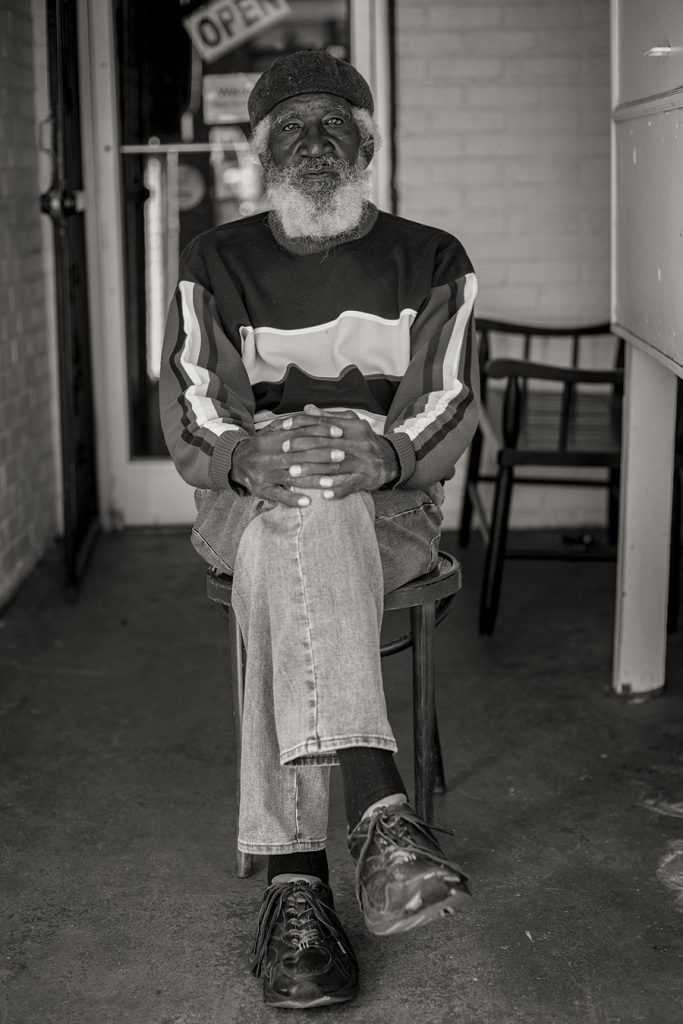

The water tower at Brown’s Ferry Water Company, top left; Sumter Cut Rate Soda Fountain, left; Todd Touchberry, the restaurant’s general manager, right.

Sumter

At the Sumter Cut Rate Soda Fountain, I meet Don, a Sumter resident of 30 years, and Todd Touchberry, the restaurant’s general manager. From its opening in 1935 until the mid-1960s there was a grill and counter with 20-something stools, Todd explains. Today, photos and paintings of regulars and accomplished Sumter natives line the walls of the restaurant, including that of The Drifters’ Bill Pinkney. The original wood floor remains.

Perched up high, Manning’s welcome sign, top left, is unforgettable. In Alcolu, a perfectly patinaed old Chevrolet truck, bottom left, catches our eye. Morning view on the Black River, right.

Greeleyville

Entering Greeleyville, a small, white abandoned cinderblock church is emblazoned with the words “True Believers” above a cross. I have always wanted to enter the doors as I pass through, and I always wondered what Sundays looked like in that place. As we got out of our car to approach the buildings, it was as if we could almost hear the preacher and a small choir singing.

Clockwise from top left: Leverne Darby has worked at Cooper’s Country Store in Salters for 47 years; his father worked there for 30 years before him. Hams are cured for 90 days. Owner Russell Cooper’s wife, Novia, minds the store. The author chats with customers at Cooper’s.

Salters

Beyond Greeleyville, an overpass in Salters looks down on an old train depot built in the 1850s. Of all the landmarks on this journey, this one most vividly stands out. We peer into the station and abandoned buildings nearby, envisioning people long ago waiting for their train.

Cooper’s Country Store is our last stop before dinner. The store was built in 1937 by former cotton farmer Theron Burrows. Burrows’ son-in-law George Cooper purchased the store in 1974, and today it is run by his nephew, Russell Cooper. As we take a look around, Cooper points to the roof and beadboard, showing us the footprint for the original store and upstairs apartment where Burrows lived with his wife and three daughters from 1937 to 1952. In a screened safe in the kitchen, hams are cured for 90 days. Out back, pigs and chickens are cooked to sell. I sit in the rockers and strike up a conversation with a man named James, who tells me he was a gospel singer in New York City.

Fishing boats line the dock near Independent Seafood Market in Georgetown, S.C., top left. Resident bird Wilbur, top right. Artist and historian Zenobia Harper at the Rice Museum, bottom left. Gullah high tea at the museum, bottom right.

Brown’s Ferry

After making our way through downtown Andrews and over to Georgetown, we meet Zenobia for dinner at the River Room restaurant. Zenobia’s mother is Gullah, with family ties to Midway, just outside of Georgetown, and the Plantersville community. After college in Atlanta, followed by a two-year stint of wonderfully scandalous things in Harlem and a few other moves, Zenobia knew it was time to return to her roots. Twenty-seven years later, Zenobia celebrates her Gullah roots through a number of avenues. She develops programming for the Rice Museum and serves as community outreach coordinator with the Charles Joyner Institute for Gullah and African Diaspora Studies at Coastal Carolina University. After sharing a meal of oysters, fish, salad and fries, we drive to the Gullah community of Dunbar, where we meet our host for the night, Janette Kennerly, who runs an Airbnb at her property on the Black River. Her grandfather and six other men bought the land before the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

After a breakfast of homemade grits, salmon patties, spicy rice with sausage and peppers, and coffee, we stop at Brown’s Ferry Water Company, which I am told is the first Black-owned business in Georgetown. Local businessman and community organizer Jerome Holmes started the water company to address concerns about the health of his community.

Andrew Rodrigues, a retired attorney and co-founder of The Gullah Museum in Georgetown, top right. A museum exhibit, bottom left. A story quilt made by Rodrigues’ late wife, Vermelle Rodrigues, which was featured in the 2013 Presidential Inauguration Parade, bottom right.

Georgetown

The Gullah Museum in Georgetown offers presentations on Gullah Geechee history, crop cultivation, animal husbandry, arts, crafts, foodways, music and more. Museum co-founder and retired attorney Andrew Rodrigues shares the story of a quilt depicting Michelle Obama made by his late wife, Vermelle “Bunny” Rodrigues. The quilt, which hangs proudly at the Gullah Museum, is part of the permanent collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and was featured in the 2013 Presidential Inauguration Parade in Washington, D.C. Andrew, a historian, activist and researcher, carries on the couple’s work, using the story quilts as a teaching tool in lectures at the Gullah Museum.

Zenobia greets us at the Rice Museum on Front Street, where Gullah High Tea is served by Jacqueline Williams and Rice Museum Director, Jim Fitch. Jacqueline shares how she was taught to make tea by midwife and herbalist Elizabeth Sumter, and shares her practice for “listening to her ancestors speak” while creating her concoctions. As we depart, Zenobia gives me a bracelet she acquired from a local antique shop.

For as long as I can remember, returning from Pawleys and Debordieu with a styrofoam cooler in tow, my family stopped at Independent Seafood Market to purchase shrimp by the pound. Since 1939, the market has been a Georgetown staple, offering fresh shrimp and seafood to locals and travelers alike. Sadly, the market has been sold to developers and will be closing for good. The longtime resident bird, Wilbur, looks into the glass door as if he knows change is coming soon — many Charlotteans will be equally devastated to learn of the market’s closing.

Later that afternoon at Kidogo Farms, amid six roosters crowing in the background Alissia Matthews explains how, after growing up in rural South Carolina, she moved to Texas to seek a better opportunity. Once tragedy struck her family — her brother lost his daughter to asthma — Matthews and her husband, Monte, decided they needed to make a change in their own environment.

About the same time, Alissia and Monte’s children proclaimed they wanted to live on a farm. “We kept dreaming it and writing it down.” In January 2020, they returned to visit family. The pandemic hit, and they decided to purchase 26 acres of pine forest from a timber company, and the children got their wish. “Being Black, Geechee and from the South, I swagger different, because I’ve always been a landowner, or I knew it was coming,” Alissia says. As she shows us around Kidogo Farms, which provides fresh produce for the surrounding community, she shares their master plan for the farm: By returning home, the couple hopes to “show their children what legacy-building looks like, and to let the land tell them what to do.”

Alissia Matthews at Kidogo Farms, left. The ruins of Old Gunn Church in Plantersville, middle. The Indiantown Presbyterian Church in Carver’s Bay, right.

Plantersville, Carver’s Bay and Indiantown

The ruins of Old Gunn Church, officially known as Prince Frederick’s Chapel, and a few miles down the road, the current chapel in Plantersville. A little red house catches our attention in Carver’s Bay, followed by a close look at Black Mingo Plantation in Georgetown County and a makeshift drive-in movie theater. The Indiantown Presbyterian Church, organized in 1757, is the oldest historical marker we see along our journey. The current structure was built in 1830. Richard uses it as an opportunity to remind me how young our country is compared to his home country of England.

The road to Black Mingo Plantation in Georgetown, left. Downtown Lake City in Florence County, right.

Lake City

Our final stop is downtown Lake City in Florence County. The small town has been revitalized, in large part thanks to the vision of local philanthropist and businesswoman Darla Moore. For 11 days in April, the city becomes a gallery during the annual ArtFields event showcasing Southeastern artists. SP

Featured Photo: An old train depot in Salters, on U.S. Route 521 east of Greeleyville, was built in the 1850s.