Tasting change in global Charlotte

July 29, 2022

by Tom Hanchett | photographs by Baxter Miller

The following adapted excerpt by Tom Hanchett is taken from Edible North Carolina: A Journey across a State of Flavor. Copyright 2022 by Marcie Cohen Ferris. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press, uncpress.org.

———

In today’s South, traditional food doesn’t just mean barbecue, collard greens and cornbread. It’s also pan dulce, cevapi, banh mi, shawarma and much more. Since the 1990s, in big cities and small towns, a wave of new immigrants has added global flavors to our regional foodways. The east side of Charlotte, North Carolina’s largest metropolis, offers a case study. In 2017 its diverse food cultures attracted scholars from the Southern Foodways Alliance, who recorded oral histories of immigrant entrepreneurs. What had drawn the newcomers to Charlotte? How did they launch businesses? What foods did they offer? How did they interact with other immigrants and with the wider city? How have foodways changed — especially as younger family members raised in the United States find their way into food-related businesses?

Desperation pushes some immigrants. Opportunity pulls others. Dino Mehic, a refugee from Bosnia, and Zhenia Martinez, who came with her parents from Mexico, personify those two extremes.

Dino bustles back and forth from his tiny Bosna Market down a step and through a door into his 10-seat Euro Grill. He takes special pride in his cevapi, the sandwich of stubby sausages that’s wildly popular in Bosnia. He’s got a smile and a wry sense of humor, but there’s an underlying sadness, too.

“My Bosnia was a beautiful country,” he says. “I left because of the war. In 1995, I lost my father in Srebrenica.” The notorious mass killing there wiped out more than 7,000 Bosnian Muslims, mostly men and boys. “I lost him. And he” — Dino’s son Mesa, who joined us for this interview — “was born in 1996. He took my father’s name.”

Dino fled to Germany, then to Charlotte. His wife found work in a local warehouse for a drugstore chain. “Then,” Dino explains, “somebody must take care of Mesa, take him to school, pick him up from school. Somebody must take care of our daughter, our home.” Was there a way for Dino to be a stay-at-home dad? “Can we open something, or do something and take care of our kids?

“When I came here I had no idea what I would do. I didn’t speak English, I needed a job, I needed to make some money. I had two family members [a wife and son, and a baby girl on the way]. All my life I am in the restaurant business and groceries, and that was my first idea, can I open a small grocery?

“The first year I went every Friday morning to Atlanta and brought stuff here. When we were beginning, I bought a van. I remember I paid twelve hundred dollars and prayed to God, ‘Come on, do not stop, please. I need you, I need you, I need you.’ That first year, every Friday I woke up at three o’clock in the morning to pick up the stuff.”

Soon Dino found a tiny storefront in a shopping plaza on Central Avenue. “All refugees, almost, were around here in Central Avenue apartments, the first two, three years. Our apartment was found for us by the refugee office; it was on Green Oaks Lane [off Central Avenue]. Many Bosnian refugees were in these apartments and the Morningside Apartments. That’s the reason why we opened on Central Avenue.

“Central Avenue at this time, it was scary. So much crime. It was not nice. There’s a lot of change. Now it’s great.”

In these same years a few blocks farther out Central Avenue, Aquiles Martinez founded Charlotte’s first panaderia, or Mexican bakery. While Dino Mehic had food experience in his previous life to draw on, Aquiles Martinez completely reinvented himself. A government bureaucrat in Mexico, he took what work he could find in menial labor after arriving in the United States. Later, a construction-related accident pushed Aquiles to learn a new trade as a baker.

“He was from a family that liked knowledge and sought knowledge,” his daughter Zhenia remembers. “In his 20s he put himself through college, studying economics. He always had books around him. In all the houses where we lived in Mexico, we had at least one wall completely covered from floor to ceiling with books. He loved politics as well. He held various jobs in government while we lived in Mexico.”

Aquiles and his wife, Margarita, a government secretary, worried for their children’s future in impoverished Mexico. “My mom said, ‘My god, how are my kids going to find a job here?’ So that’s when they decided to move us to the U.S.”

Zhenia Martinez

They settled first in Columbia, S.C., where a relative ran a Mexican restaurant. “They worked as cooks. They did the prep work and line work and even, when necessary, dishwashing. I don’t think they ever saw it as bad work. It was an honest way to make a living and feed your family.

“They came here with visas, but they overstayed their visas. Luckily, with President Reagan’s amnesty program in 1986, they got papers. That’s when they brought us. My brother and I stayed with my maternal grandmother in northern Mexico for about a year.

“My dad found work in construction; my mom worked in a factory. While my dad was working, he fell from a second floor. He couldn’t keep working in construction. In his fifties, he had to find another way to make a living.

“He started selling Mexican products out of a van. He had driven through the small farming towns of North Carolina and South Carolina. He saw a growing Latino population.

“One of the things he bought was pan dulce,” the sweet pastries beloved in Mexico. “When he saw how much people looked forward to that, he decided to open a bakery.”

But neither Aquiles nor Margarita Martinez knew anything about commercial baking.

“They went to Mexico to Chihuahua to a small bakery which still had a brick oven. They said, ‘We want to learn. Will you teach us?’ They were there for six months, and they learned everything that they could about pan dulce.

“The variety of pan dulce, it’s crazy. I’m trying to grasp a number — maybe about a hundred different ones? There are 10 doughs, and from those doughs you make the different breads. The thing about pan dulce is that it’s artisan made. You could never make it with a machine. It’s so artful. Anyone that underrates the pan dulce should spend a day trying to make it and have it come out beautiful. Everything has to be shaped by hand.”

Where to launch their shop? Charlotte’s Latino population was growing rapidly in 1997, and there was an inexpensive space for rent on Central Avenue. Aquiles and Margarita Martinez named their new bakery Las Delicias, in honor of Margarita’s Mexican hometown of Delicias. “That was the first Mexican bakery in Charlotte. I remember the first spring they opened, my aunt was here, my father’s sister. We literally sat at the door waiting for customers, because nobody would come in.”

The customers eventually did come — not only Mexican immigrants but migrants from every part of Central and South America. Today the panaderia is known as Manolo’s, led by Manolo Betancur, who is from Colombia. Zhenia Martinez reflects, “What started out as a Mexican bakery is now a Latin American bakery. In Charlotte as we’re growing so intertwined, we’re seeing the influx of other cultures and the sharing that results. We’re growing as a global culture and as a global business. We do not tailor our business to just one customer but rather to everyone.” SP

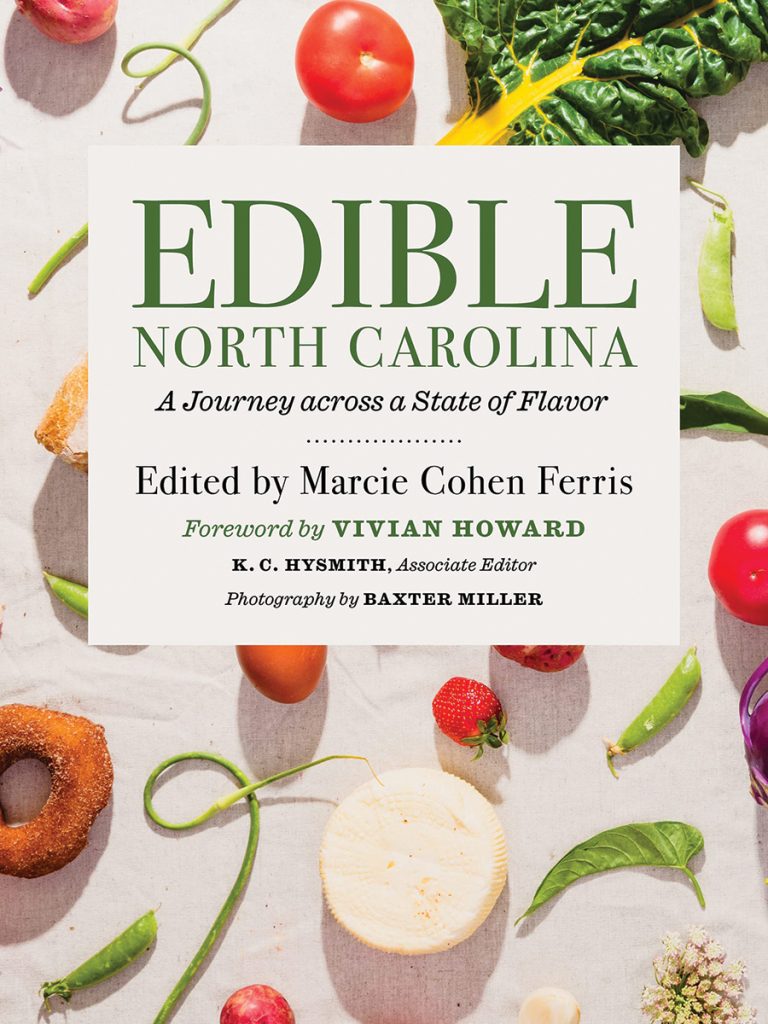

Edible North Carolina is an anthology of essays along with photographs and 20 recipes highlighting the state’s diverse food landscape. The book tells the stories of the people behind the plates, from fishermen to farmers to restaurateurs from the coast to the mountains, providing a historical context that informs today’s contemporary food scene. Contributors include Charlotte area food writers Keia Mastrianni and Kathleen Purvis, acclaimed Triangle chefs Cheetie Kumar and Bill Smith, and Durham chef and James Beard Award winner Ricky Moore. — Cathy Martin

Featured photograph: Marranitos de piloncillo, Manolo’s Latin Bakery