Peak growing season

March 30, 2020

The owners of TimberTop Garden in Blowing Rock take gardening to the extreme.

By Ross Howell Jr. • Photographs by Sam Froelich

Google “extreme gardening” and you’ll get some tantalizing results — how to create an organic garden in the Southwestern desert, for example, or how to grow perennials in the Alaskan wild.

But if your search algorithm doesn’t yield the garden Monica Perry has created in Blowing Rock, it really should.

Perry’s magnum opus clings to a five-story section of a precipitous sandstone face of the Johns River Gorge, the site of an old-growth forest and the Johns River headwaters, lying some 3,000 feet below the town.

I’m sitting in the living room at “TimberTop,” Monica and Chip Perry’s home. To my right are large windows overlooking a deck. Window boxes mounted along the railing dazzle with red petunias, gold and magenta cockscombs, sweet-potato vine, and more. At least a dozen hummingbirds dive and flash between feeders placed among the flowers.

Beyond lies the grand, blue expanse of mountains and sky.

Monica Perry comes in her eyes the color of the pale blue view out the windows.

“I didn’t even have time to get the dirt from my fingernails,” she says, holding out the strong hands of a gardener for me to inspect.

“Oh, I’m a North Carolina mountain girl through and through,” Perry says. Her mother’s people — Scots-Irish, with a great-grandmother who was Tuscarora — were from Little Switzerland, about 45 miles southwest of here. As a young girl, Perry spent time in Mitchell County. But most of her growing up was done in Catawba County. She studied speech language pathology at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, and for 21 years, she worked as a speech therapist.

The house was built in 1946 by J.E. “Ed” Broyhill, the founder of Broyhill Furniture Industries, and his wife, Satie. The first major garden project on the property was initiated while the Broyhills were owners.

As the story’s told, Satie Broyhill was concerned that she might not be invited to join the Blowing Rock Garden Club because, well — she didn’t have a garden.

TimberTop was connected to the road by a wooden platform used to park cars. The Broyhills had the wooden platform removed. Steel beams were installed, over which a concrete pad some 2 feet thick was poured. A hole was left in the concrete to accommodate an old hardwood growing between the house and road.

Topsoil was hauled in, and voilà! Satie had her garden.

Intervening owners had left the tree growing through its concrete collar when the Perrys bought the house in 2007. Sadly, an arborist called in to examine the old tree’s root system determined it was too far gone and needed to be removed.

Monica found an enormous copper kettle once used to cook apples and had it placed over the hole in the concrete to serve as a planter. We walk by it as we start our garden tour. The kettle is loaded with bright flowers and resonates with the hum of a multitude of happy pollinators flitting about. Along the front of the house, there are big earthen planters with an abundance of flowers. There’s a space of green grass where Monica tells me her Boston terriers like to play.

“It’s gated and fenced, so it’s safe,” she says. She points out the stone pillars of a fence along the road, joined by beautifully styled metal sections.

“When they were rebuilding the road, they wanted to install those galvanized guardrails you see on the highway,” Perry says. She was able to convince the town to let her install (at her own expense) the attractive fence standing there now.

As we walk onto the road, Perry points out how she also landscaped the mountainside rising nearly vertically opposite the house.

“See the ground cover?” she asks, then tells me she had more than 12,000 pachysandra set along the roadside and up the bank. I ask her to repeat the number, because I can’t believe I heard it correctly.

In the dappled sunlight by the road are wild geraniums, heartleaf brunnera and native ferns. Perry points out the mossy face of an escarpment above the road. She tells me she had the stone sprayed with three different moss “milkshakes” until the moss finally took. Farther up the rock face we can see wild ginger and Solomon’s seal, shaded by mountain laurel and native buckeye trees.

Now we’re at the place in the road where the story of Monica Perry’s extreme garden begins.

On July 4, 2013, the town of Blowing Rock saw fierce thunderstorms and flash floods, including the section of the two-lane road next to TimberTop.

The road collapsed, sending earth and boulders tumbling into the gorge below. What remained was a gash in the mountainside, tangled with tree roots and debris.

Monica Perry resolved not only to restore it, but to improve it. She hired stonemason David Mason of nearby Todd to begin rehabilitating the mountain. In just over a year’s time, Mason and his crews brought in some 270 tons of concrete and stone to the site. Yes, I asked Perry to repeat that number, too.

We peer over the edge of the precipice. I’m only able to discern concrete where Perry points it out to me, so cleverly is it formed to simulate original stone. Boulders — some of them cantilevered into the mountain and strengthened with rebar — are placed strategically to support planting areas. Perry tells me about the hidden metal cleats used to secure belaying lines when her gardeners tend some of the more precipitous spaces.

I’m flummoxed by the magnitude of what she’s describing.

“Monica,” I venture, summoning the courage to ask, “was there ever a morning when Chip looked at you over breakfast and asked if you’d completely lost your mind?”

“No,” she answers matter-of-factly, “because he has his cars.”

A Harvard MBA, Chip Perry was the first employee of Autotrader.com and went on to become CEO of the company, which was later sold. He recently retired from another auto-related online company, which he also headed. Chip maintains a private collection of automobiles in Blowing Rock.

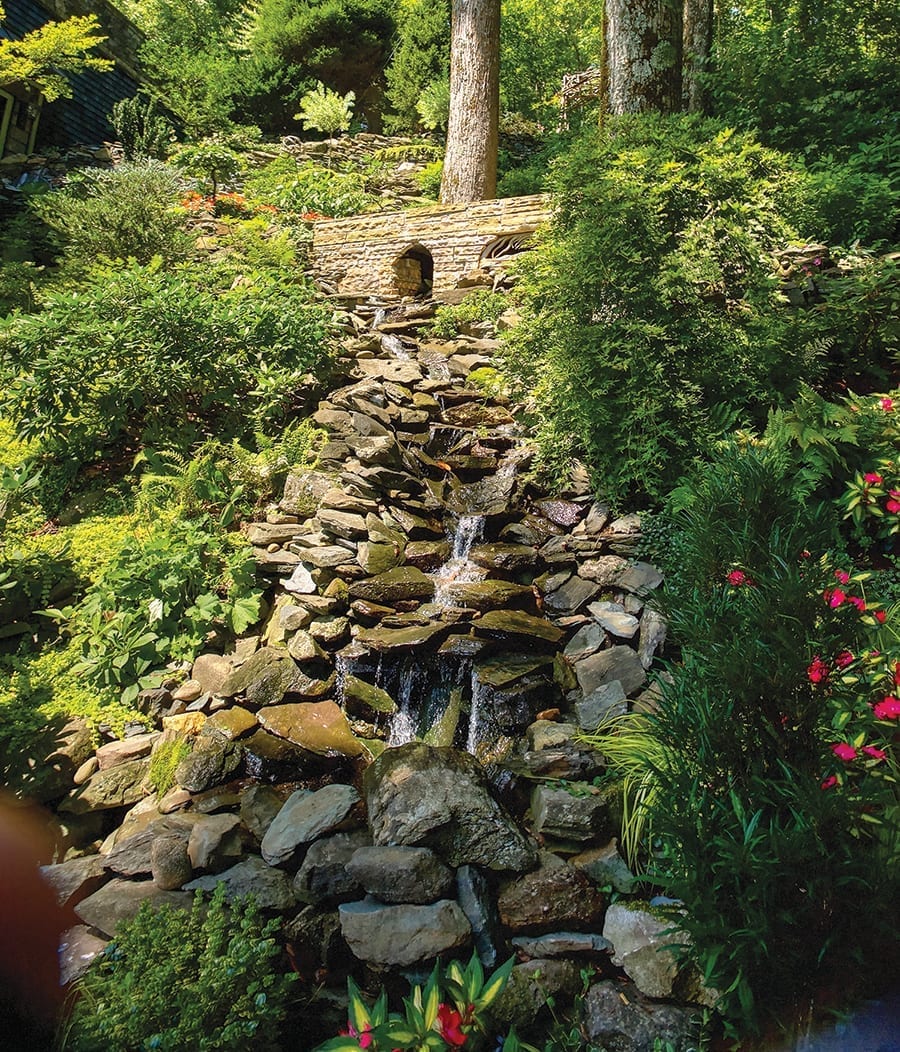

We turn from the gorge and walk the length of the house to its other side, where a natural wood lattice overhangs the entrance to a stone path. As we step through, I can see into the forest way below the house. A stream descends the steep incline, crisscrossing in stages, as does the path before us.

Monica points out the lime-green color of the trim on the house.

“There was quite a discussion about that,” she says, smiling. “It’s my favorite color, and if you have a shady garden spot you want to brighten up, there’s nothing better for it,” she continues.

To settle her point, she directs my attention to a shaded terrace above the path. It’s brightened by lime green creeping Jenny. I nod in agreement.

She tells me when she started planning a path here, there was nothing except a few trees.

“See the maple there?” she asks. She tells me she would crawl — because of the steep incline — to the tree and hang onto it, mapping in her mind’s eye a path down. Now we descend its stone steps to a pleasant stop she calls the Shade Terrace.

The terrace features a handsome stone bench overhung by native witch hazel. Perry shows me the metal support she had added to help the plant withstand winter winds and snows.

We pause for a moment. She explains that the whole garden — now comprising five stories — was designed in this way.

“I didn’t have a master scheme,” Perry says. “We’d just build a path to somewhere, and then we’d build another.”

We make our way down the path toward the pond, listening to the play of water in the stream. As we near the pond, the surface roils with activity. Perry’s koi are hungry, and they’re making sure she understands.

They’re beautiful fish. Some are bright orange with ink-blue patches, some are orange and white, others are bright gold. There are 20 of them, Perry tells me, each named with monikers like Marilyn, Diamond Jim, Sunshine, Molly Brown, Peepers and Lady Chablis — a platinum-colored fish with pale blue eyes, Perry’s favorite. There are heating rods at the pond’s bottom to ensure it won’t freeze solid in winter.

As we approach a spot just below an area designated the Sunset Terrace, the gorge falls sharply from the pathway, and there is no railing to hold onto. I’m fairly good with heights, but if it’s not vertigo I’m feeling right now, it’s vertigo’s first cousin.

I step back from the edge, focusing on the near-at-hand. I count six tiger swallowtail butterflies perched high on a blossom of Joe-Pye weed overhanging the path. Intoxicated with nectar, the butterflies are oblivious to us. A chorus of other pollinators drone in blossoms on other stalks of the Joe-Pye, and a black swallowtail flicks its wings on a blossom at the very top of the plant.

On various paths, there are cockscombs in a variety of colors, creeping Jenny, black-eyed Susans, and other bright flowers scattered in planting areas by bare rock faces, along with azaleas, “Brass Buckle” Japanese holly, “Lion’s Mane” maples, and buckeye trees. We cross Perry Pass, a cliff of native rock jutting from the face of the gorge — where I’m especially grateful for the newly installed metal-and-rope hand railings — to see the Secret Garden, a secluded little terrace with stone benches and a fire pit overhung by native rock.

We head back toward the house by way of the Path to Nowhere, which is where Perry’s “gazebo” was built.

It was quite a project. Pilings were jackhammered in, building materials lowered by crane and concrete carried down the gorge by hand. It is one of the most beautiful rooms I’ve ever seen, featuring on one side a breathtaking view of the gorge; on the other, a view of the massive, mossy rock face on which the house is built, with native rhododendrons shading a pair of enormous Jack-in-the-pulpits.

As we near the back deck of the house, we see Anne Calta, Perry’s gardener, and Ryan Visingard, her assistant.

“This wouldn’t be possible without them,” Perry says. “They manage the garden day-to-day and when Chip and I are traveling.”

As I prepare to leave, Perry tells me she’d like to show me a special place. Near the midpoint of the second-level deck of TimberTop are two big chaise lounges.

“We’d make up one of the chaise lounges for my mother when she visited,” Perry says. “She always slept out here. We lost her two years ago.”

She tells me how proud her mother was of what she and Chip had accomplished at the house and garden, and how whenever she was coming to visit, she would ask on the phone, “Do you have my bed made yet?”

I step to the railing. The view where the chaise lounges sit is dizzying: The rock face plummets away from us. The gorge turns sharply toward the house, ending right below where we stand.

I spot what I believe to be a red-tailed hawk veering over the dark green canopy of trees in the gorge. It’s hundreds of feet below, hunting just as its ancestors had when this was the land of the Cherokee. Closer by, I admire the contrast of Perry’s bright flowers with the warm-colored stone walkways of her garden.

Classical Roman religion described an element of landscape called genius loci, a protective “spirit of a place.” As I gaze over the mountains from this vantage, I feel certain such a spirit stands guard here.

Weeks later, I find my thoughts returning to Perry’s garden. Is she taking a respite from spreading mulch to watch cloud shadows drift over the treetops of the Johns River Gorge? Or feeding her beautiful, gluttonous koi in the pond? Is she weeding flowers on a precipice, a belaying rope tied snugly about her waist?

Monica Perry is the person who introduced me to the concept of “extreme gardening.”

And I’m grateful. SP